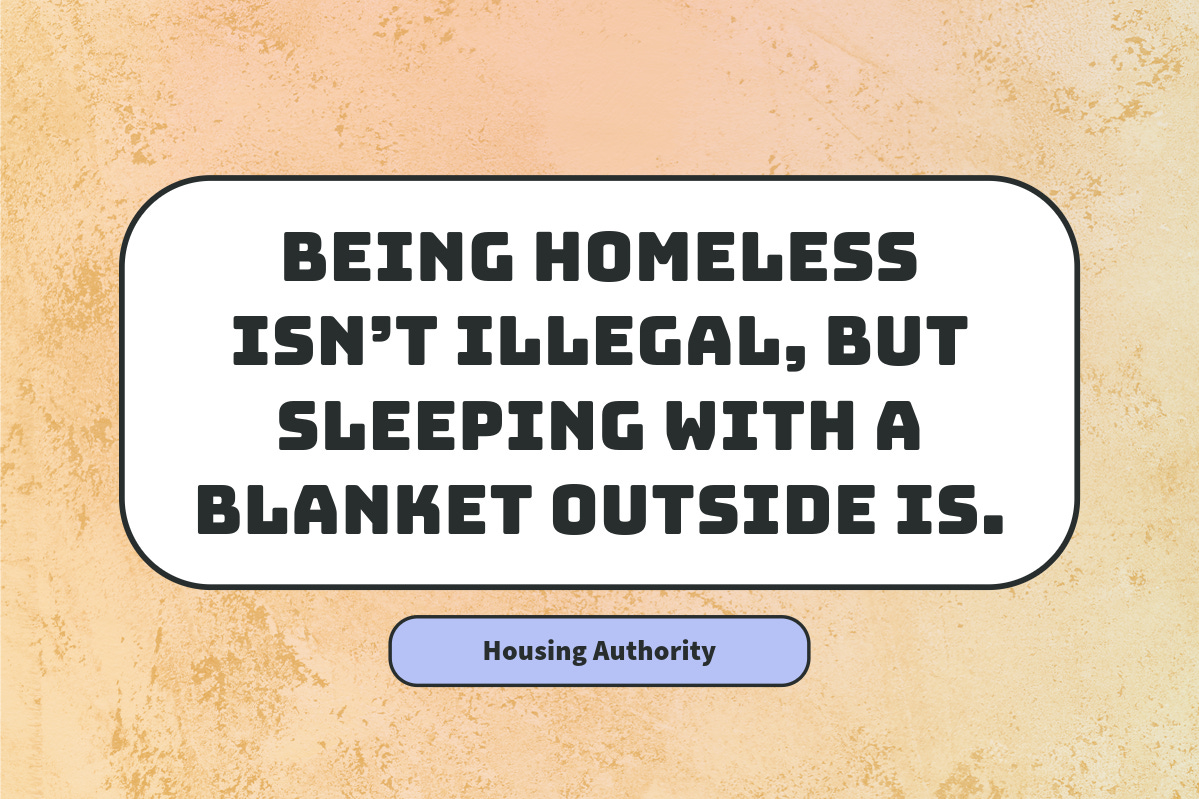

Being homeless isn’t illegal, but sleeping with a blanket outside is.

Grants Pass V Johnson. It is so ordered 🔍

I don’t typically follow The Supreme Court because I think it kinda sucks as an institution. Unfortunately, between Dobbs, this Grants Pass ruling, and the most recent case involving the National Labor Relations Board, I’ll need to follow along more closely.

I spent the first few hours of my Friday morning, scrolling through the opinions on the Grants Pass V Johnson ruling trying to better understand how we got here. This was a 6-3 ruling along the expected ideological divide that effectively criminalizes homelessness.

Unfortunately, (again), there are a lot of things to hate. I’ve pulled several quotes that I found particularly heinous — no rage bait intended just a somber recognition of how we are failing our more vulnerable.

Also, it’s worth noting that I am not a judge or a lawyer. I am just a housing policy person who happens to live in Oregon.

Cities argue that they need to be able to arrest people who camp regardless of anything. Being homeless isn’t illegal, but sleeping with a blanket outside is.

“Grants Pass’s public-camping ordinances do not criminalize status. The public-camping laws prohibit actions undertaken by any person, regardless of status. It makes no difference whether the charged defendant is currently a person experiencing homelessness, a backpacker on vacation, or a student who abandons his dorm room to camp out in protest on the lawn of a municipal building.”

I just found it interesting to see the student protests being mentioned in this case. Oral arguments occurred in mid-April as the student protests at Columbia and around the country were escalating. Also notable, this would apply to other public occupation protests like any autonomous zones or Occupy Wall Street.

“[San Francisco] “uses enforcement of its laws prohibiting camping” not to criminalize homelessness, but “as one important tool among others to encourage individuals experiencing homelessness to accept services and to help ensure safe and accessible sidewalks and public spaces.” San Francisco Brief 7. (Pg 9)

The words “important tool” are doing a lot. I don’t see how arresting people, putting them in jail, and levying fees on them improves their access to housing or helps them afford their housing.

There are many comparisons between specific court cases around substance abuse as the Court tries to separate involuntary behavior and status.

“In Powell v. Texas, 392 U. S. 514 (1968), the Court confronted a defendant who had been convicted under a Texas statute making it a crime to “‘get drunk or be found in a state of intoxication in any public place.’” Id., at 517 (plurality opinion). Like the plaintiffs here, Mr. Powell argued that his drunkenness was an “‘involuntary’” byproduct of his status as an alcoholic.” (Pg 22)

The focus here on “involuntary behavior” comes from the plaintiffs (homeless folks being criminalized) who argued because Grants Pass has no shelters, they are “involuntarily camping.” In doing this, they’re about to set up this argument to walk back Martin V Boise.

Start with this problem. Under Martin, cities must allow public camping by those who are “involuntarily” homeless. 72 F. 4th, at 877 (citing Martin, 920 F. 3d, at 617, n. 8). But how are city officials and law enforcement officers to know what it means to be “involuntarily” homeless, or whether any particular person meets that standard? Posing the questions may be easy; answering them is not. Is it enough that a homeless person has turned down an offer of shelter? Or does it matter why? Cities routinely confront individuals who decline offers of shelter for any number of reasons, ranging from safety concerns to individual preferences. See Part I–A, supra. How are cities and their law enforcement officers on the ground to know which of these reasons are sufficiently weighty to qualify a person as “involuntarily” homeless? If there are answers to those questions, they cannot be found in the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause.” (Pg 26)

I think answering it is very easy. Homeless folks had their housing taken away from them in the form of eviction, rent hikes, harassment, the death of a loved one, and a myriad of other forces that push people onto the streets. That seems pretty involuntary to me, but I’m not Gorsuch.

“By imbuing the availability of shelter with constitutional significance in this way, many cities tell us, Martin and its progeny have “paralyzed” communities and prevented them from implementing even policies designed to help the homeless while remaining sensitive to the limits of their resources and the needs of other citizens.” (Pg 29)

The “constitutional significance” refers to other examples from court cases that require sanctioned camps that have increased in the past few years to have access to plumbing and social services. This is just complaining from cities that you can’t just round up all of the homeless people and stick them in a fenced area, they need to have access to things that survival requires.

Justice Thomas continues to question rulings from decades ago in his concurring opinion.

“In Robinson, the Court held that the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause prohibits the enforcement of laws criminalizing a person’s status. Id., at 666. That holding conflicts with the plain text and history of the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. See ante, at 15–16. That fact is unsurprising given that the Robinson Court made no attempt to analyze the Eighth Amendment’s text or discern its original meaning. Instead, Robinson’s holding rested almost entirely on the Court’s understanding of public opinion…” (Pg 1)

Robinson was the case in which the Court held that laws criminalizing the "illness" of narcotic addiction inflicted cruel and unusual punishment. Saying Robinson was a matter of public opinion is a choice.

Nice analysis. Unfortunate situation where cities engage in this kind of behavior.