The housing crisis needs no introduction — it’s bad out there! We all know rents are skyrocketing and starter homes are going for $400,000. Like some friends of ours just bought the jankiest house that wasn’t even move-in ready with a price tag of over $450,000. And we can see the visible poverty that housing insecurity creates with the number of tents popping up in parks and freeway medians.

I was telling my brother when I was home for Christmas the more I learn about “the housing crisis” the more I realize just how bad it is. It’s bad because our housing system has several competing and contradictory motives.

Housing means many things to different groups. It is home for its residents and the site of social reproduction. It is the largest economic burden for many, and for others a source of wealth, status, profit, or control. It means work for those who construct, manage, and maintain it; speculative profit for those buying and selling it; and income for those financing it. It is a source of tax revenue and a subject of tax expenditures for the state, and a key component of the structure and functioning of cities.1

There’s a power analysis within this matrix that will illustrate how housing as the site of social reproduction becomes devalued when there’s money to be made. We’ll get to that.

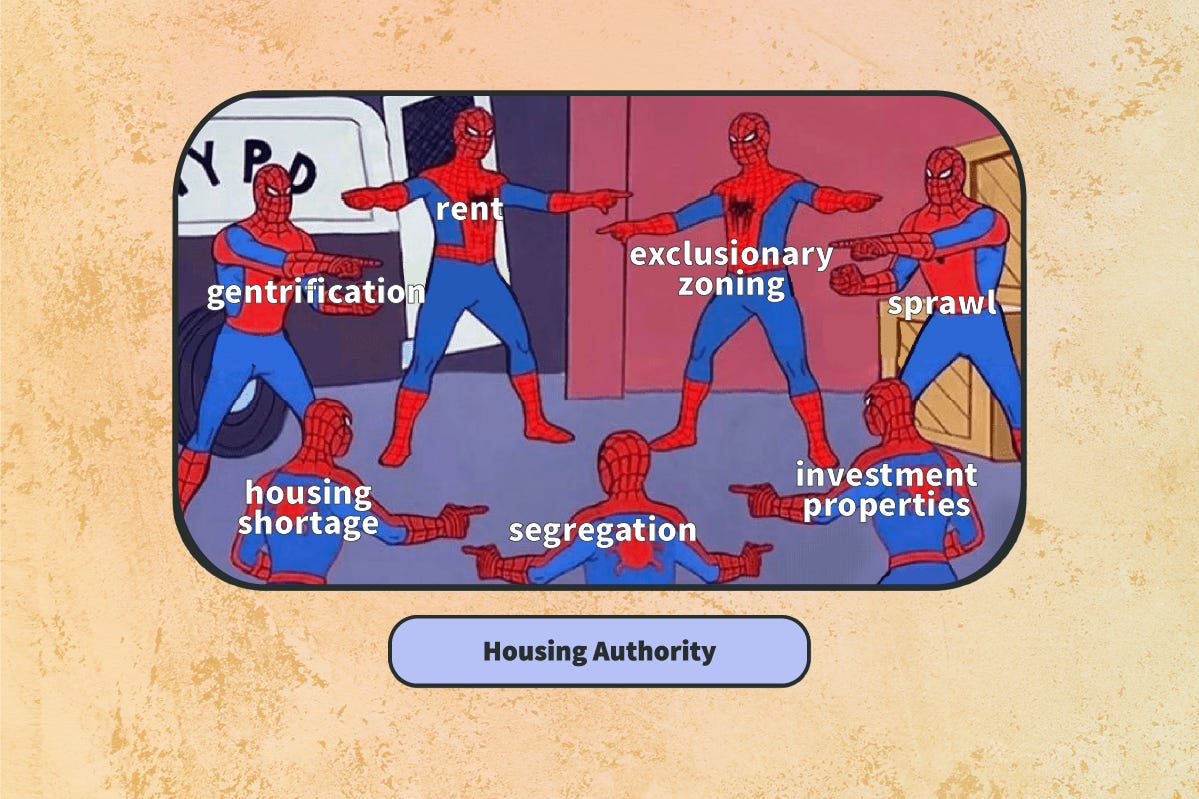

The many parts of “The Housing Crisis”

UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute published a compelling blog post a couple of weeks ago that looks at “the housing crisis” as 13 dysfunctions swirling around each other.2 I think this makes a lot of sense when we accept that housing has many different purposes.

According to the article, these are the 13 different crises:

There is a lack of housing available to lower-income and low-wealth individuals and families.

The median (or mean) price of housing has become too expensive.

There is a severe “rental housing crisis.”

There is a housing production deficit problem, also known as the “building crisis,” or the “housing shortage.”

There is a jobs/housing imbalance problem.

There is a related problem of the jobs/housing fit.

There is the problem of sprawl.

There is an eviction crisis.

There is a homelessness crisis.

There is a gentrification and displacement crisis.

There is a worsening racial divide in homeownership rates.

There is a serious problem of exclusionary zoning.

There remains a fair housing crisis.

💡 Gut check: What are your initial thoughts about this list?

The major elephant in this^ list 💸

In non-leftist media, there is a conspicuous refusal to acknowledge class and neoliberalism’s role in our housing issues. But on the left, we often fall into the trap of blaming capitalism and its subsequent issues as the reason for our housing woes. I’m guilty of it. It’s snappy online, and a convenient verbal short-hand when talking to people who already get it. But it’s frankly ahistorical and poor material analysis.

Underneath the 13 specific housing issues is an undercurrent of housing commodification that pits people who need housing (everyone) against those who are using housing as a means of making money. The theft of the commons, or land that was communally used and regulated, was an important step towards modern capitalism and the commodification of housing. (For further learning go read about primitive accumulation3 and the privatization of the commons.4)

Money and property give people a lot of power. When housing is commodified aka when housing is exchanged on the basis of making people money, those with the real estate assets have the power to improve their assets through state policies. This is both intentional and a sign that the housing market system is working as it should.5

This has resulted in things like the mortgage interest tax deduction and zoning that only allows for low-density, single-family homes. And these policies contribute to rising home values, increased real estate speculation, excessive suburban sprawl and a housing shortage.

As rent prices follow housing prices, systemic displacement and eviction are used by landlords and developers who want to cash in on higher rents, which then cause increased real estate speculation, and higher property values (and even higher rents). As this snowballs, we get the homelessness, displacement, and eviction crises.

Capitalism meets white supremacy

However we don’t just live in a hellscape brought on by unchecked housing commodification, we also live in a racial capitalism hellscape. White supremacy forms the foundation and rationale for many of our housing disparities.6

Redlining and segregation created lasting scars in our cities.7 Redlined Black neighborhoods were considered “hazardous” to private developers and municipalities and therefore received very little investment from cities in the form of public services (schools, parks, hospitals, transit).8 The poor property values also attracted mass displacement events like freeway expansions and contributes to the gentrification and slumification cycle. While it is illegal to discriminate in renting and lending based on race these days, discriminating based on class is still allowed, and as expected, still falls along racial lines.

Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color are disproportionately more likely to remain life-long renters and lose their homes when they do manage to buy one.9 When you hear non-profits like the one cited here talk about racial disparities in housing access, I want you to understand this means that the exploitation of BIPOC tenants creates the equity landowners profit from. The wealth has to come from somewhere.

(I have purposely left out #5 and #6 from this discussion because I see the relation between labor and housing as separate from the commodification issue. I’ll get to that in another newsletter.)

Fighting the housing crisis

I mostly agree with the two arguments the original blog post asserts: (one) that “there are a cluster of dysfunctions and disturbing circumstances” within our housing markets, that many of these dysfunctions are intertwined; (two) that many efforts at solving these dysfunctions have made other housing problems worse.

When we flatten the housing crisis as simply “a supply issue” or “an access problem” then we miss out on the ways some of these issues compound and contradict. Like open season home building will result in mass displacement and exacerbate racial segregation. Making rents affordable will not magically rehouse homeless people or stop people from becoming homeless.

So we need to look beyond policies that alter market incentives and provide half-baked protections. We have to fundamentally change how we conceptualize our housing system. This looks like building power within the tenant class to demand the end of our exploitation.

In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis by David J. Madden and Peter Marcuse, pg. 11

Deconstructing the 'Housing Crisis' by Stephen Menendian

The Secret of Primitive Accumulation by Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Part 8

The Theft of the Commons by Eula Biss

In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis by David J. Madden and Peter Marcuse, pg. 10

Understanding Exclusionary Zoning and Its Impact on Concentrated Poverty by Elliot Anne Rigsby

The Lasting Legacy Of Redlining by Ryan Best and Elena Mejía

The Lasting Impacts of Segregation and Redlining by Jeramy Townsley, Unai Miguel Andres, and Matt Nowlin

Racial Inequities in Housing from Opportunity Starts at Home